Negligence Leads to Aspirated Foreign Object and Lawsuit

Case Study

Marc Leffler, DDS, Esq., & Mario Catalano, DDS, MAGD

September 7, 2022

Reading time: 9 minutes

Background Facts

Dr. H, a pediatric dentist in a rural area, saw a 13-year-old male patient whom she had treated since he was about 5. Over the years, his treatments consisted solely of periodic prophylaxis and a few sealants. At this visit, the patient’s mother recounted that he had been struck on the upper lip with a baseball several months prior. Although the lip had swelled at the time, no dental symptoms had occurred until a few days before the office visit, when tooth 9 — the upper left central incisor — began to hurt.

Dr. H updated the patient’s medical history, gathered more details about the baseball incident, took a periapical radiograph of the upper anterior region, and performed vitality testing of the upper incisors. The symptoms and examination results indicated that tooth 9 needed endodontic treatment. After Dr. H explained the endodontic process and what to expect following it (in terms of restoration and tooth longevity), the patient’s mother agreed to have Dr. H proceed.

Upon receiving the local anesthesia infiltration, the patient squirmed in the chair, but generally tolerated it. However, when Dr. H approached him with a rubber dam and began to place it, the patient became scared and pushed the dentist away. Dr. H explained to him why she needed to place the dam, and then she tried again. The patient continued to push it away and yell that he did not want it in his mouth. Dr. H tried a third time (while administering N2O/O2 by nasal hood), but was still unsuccessful. She then decided to go forward without a dam in place.

The patient became agitated as Dr. H gained access into the pulp, but she was able to complete that step. Once the filing began, the patient responded by moving around, flailing, and yelling. Dr. H lost control of the #10 file in her hand and dropped it into the patient’s mouth, where it traveled toward the oropharynx.

Dr. H firmly told the patient that he needed to stay still as she tried to grab the file with college pliers, but he continued his previous behavior and began coughing incessantly. Dr. H eventually lost sight of the file. She was able to calm the patient by telling him “I’m not doing it anymore,” which allowed her to place suction as far posteriorly as she could. Although the patient’s coughing subsided, Dr. H was unable to locate the file.

The closest hospital was about 40 minutes away, so Dr. H told the patient’s mother to take him to a free-standing medical office down the street. Dr. H did not call ahead to alert the medical office of the patient’s condition or imminent arrival. After a 30-minute wait at the medical office, a chest X-ray was taken that showed a foreign object in the right main bronchus. The physician was unsure about what he saw, so he sent the patient to the hospital and simultaneously emailed a digital version of the film to its emergency department (ED). When the patient arrived at the ED, another chest X-ray was taken that revealed the aspirated dental file in the right lung.

Once an appropriate amount of time had passed to ensure that the patient’s stomach was empty, the on-call pulmonologist performed a bronchoscopy under general anesthesia and retrieved the file. The patient remained in the hospital until the following evening and then regularly followed up with the pulmonologist. He reported shortness of breath, frequent coughing, and chest discomfort for months. The pulmonologist stated that no treatment was indicated and noted that the patient could potentially experience the symptoms indefinitely.

Legal Action

The patient’s family retained an attorney to seek compensation for what the patient had endured and for his ongoing symptoms, which did not seem to be improving. Before filing suit, the plaintiff’s attorney contacted Dr. H’s malpractice insurance carrier to discuss the situation, claiming that Dr. H was negligent in performing endodontics without a rubber dam (especially on a scared child), and in failing to take any other measures to protect against a swallowing or aspiration event.

The plaintiff’s attorney would not agree to any settlement until it could be determined whether the patient’s ongoing symptoms would be long-term or permanent. (The extended statute of limitations for minors in many, if not all, states allows more than ample time to take a “wait-and-see” approach regarding any longstanding effects.) Approximately 1.5 years after the incident, the patient was able to resume normal activities, and he voiced no further issues.

At that point, the plaintiff’s attorney filed a lawsuit. The malpractice insurance carrier obtained Dr. H’s consent to settle the case (an allowance that her policy contained). The plaintiff’s attorney then worked with the carrier’s claims representative to reach a settlement agreement that satisfied the patient’s parents as well as the court, the latter of which is frequently required in cases involving injured minors to ensure that settlement funds are appropriately set aside for the child and that the magnitude of the injuries is fully known to the extent reasonably possible.

Risk Management Considerations

Theodore Passineau, JD, HRM, RPLU, CPHRM, FASHRM

The first issue to consider in relation to this case is informed consent, the requirements of which vary among states. Generally, prior to invasive procedures, dentists are obligated to advise a patient (or a minor patient’s parent or legal guardian) of the foreseeable risks of the proposed procedure, its expected benefits, and any reasonable alternatives. This discussion should take place before obtaining consent or refusal to move forward with treatment.

An important consideration in this case is whether aspiration of a dental endodontic file is a risk that is foreseeable — a determination that dentists must decide for themselves. Traditionally, foreseeable risks are viewed as those that are known to occur in the absence of negligence; however, as with many legal concepts, the definition is not precise. Because of this, dentists often are left to determine whether such a pre-procedure warning is appropriate.

From a risk management perspective, providing more information to patients to help them make better decisions is generally recommended. However, obtaining informed consent does not absolve dentists from liability if they fail to comply with the standard of care, and patients cannot “sign away” their rights to have non-negligent treatment.

Another issue in this case was the rubber dam. Many dentists do not use rubber dams during root canal therapy or related procedures due to personal choice, impossibility in placement, or patient intolerance. However, experience shows that plaintiffs can easily find expert witnesses who will testify that the failure to use a rubber dam for endodontics is a departure from the standard of care. Defendant dentists, on the other hand, might face an uphill battle finding credible experts to testify in support of them, especially when no other protective measures were in place to counter the risks of swallowing/aspirating a foreign object or preventing potential infections.

In this case, Dr. H decided to proceed with treatment without a rubber dam in place, rather than deferring treatment until she could take a safer approach. Alternative approaches include pre-procedure sedatives, performing the treatment in a hospital under general anesthesia, performing the treatment in the office with a practitioner who is skilled in sedating or generally anesthetizing children, or employing some other means of mitigating the child’s intolerance.

Dr. H also did not use any other precautions, such as setting up a gauze barrier to catch a foreign object forward of the oropharynx, tying a piece of dental floss through the hole in the file’s handle to assist in easy retrieval should the file slip, or using one of the other protective devices available on the market. As such, Dr. H compromised her initial plan without considering her other options.

A final and important point relates to the personal relationship between dentists and patients — a critical part of dental practice. At a time when the patient and his mother were understandably upset, and the patient was in some degree of distress, they were left to travel to the local medical office and then to the hospital on their own. Had Dr. H or a member of her staff accompanied them, it likely would have had some calming effect, and it certainly would have communicated Dr. H’s concern for her patient. Whether that would have changed the family’s decision to retain an attorney and to proceed as they did cannot be known. However, dentists often can assuage situations when they demonstrate that they care about their patients by regularly communicating with them during treatment periods, especially when problems or complications arise.

Summary Suggestions

The following suggestions may be helpful to dentists seeking to minimize their patients’ risk of a swallowing or aspiration event:

- Recognize that a variety of foreign objects can be swallowed or aspirated, including implant materials; tooth fragments; orthodontic wires, brackets/bands; crowns; repair materials; and pieces or the entirety of a bur. The potential for foreign object swallowing or aspiration affects nearly all types of dental practitioners.

- Evaluate all patients to determine their appropriateness for treatment at the time of the procedure. Patients who are sedated and/or under general anesthesia lose their protective pharyngeal reflexes, so particular care should be taken to prevent objects from falling to the back of the mouth.

- Follow simple safety precautions to prevent the swallowing or aspiration of a bur. First, never reuse single-use burs. These burs are not designed to withstand the temperatures associated with sterilization, which makes them more prone to breakage when they are reused. Second, be sure that the bur is fully seated in the handpiece prior to use and that the handpiece’s gripping mechanism is functioning properly. Run the bur briefly prior to entering the oral cavity, and away from the patient’s face, to make sure that it is not loose.

- Use retrieval methods to assist in preventing the swallowing or aspiration of a foreign object. If the instrument you are using has a retrieval hole (e.g., on endodontic files and reamers) or a slot (e.g., on implant hand instruments), be sure to place a piece of dental floss through or around it to assist in retrieving the object if it slips. Crowns are smooth and can easily slip out of your fingers, and teeth are known to break during extraction or slip from forceps. Tying floss around crowns and teeth is not viable, so other protective means — such as oropharyngeal gauze barriers or rubber dams (when appropriate) — are critical.

- Employ alternatives to rubber dams when patients will not tolerate them or other circumstances prevent their use. Understandably, rubber dams make many patients feel claustrophobic, which could result in irrational behavior or a medical emergency.

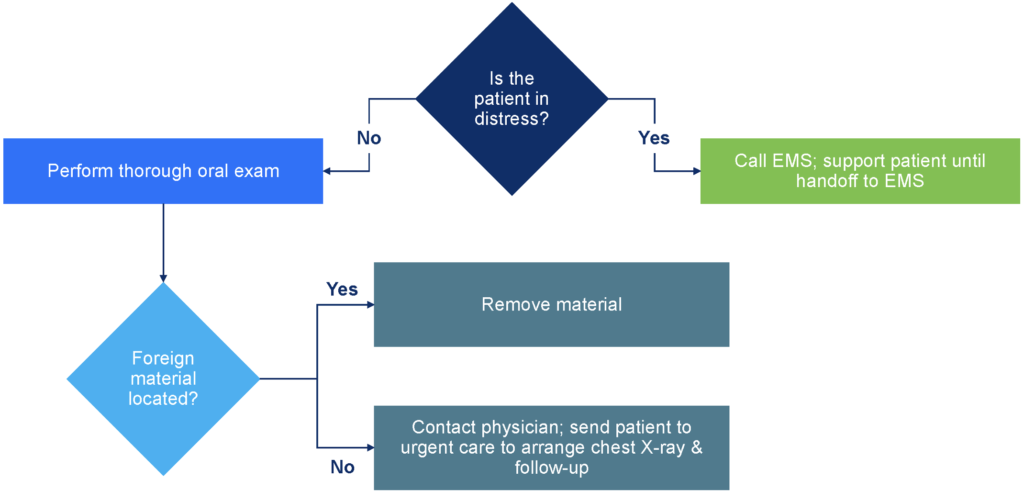

- Keep MedPro’s swallowed/aspirated foreign object protocol close at hand in case swallowing or aspiration does occur (see appendix). A prompt and appropriate response to this event can be beneficial in minimizing the degree of injury.

Conclusion

Not all adverse events that occur in the practice of dentistry can be avoided. Yet, events that occur with regularity should be anticipated, and reasonable steps should be taken to prevent them. Similarly, when adverse events do occur, prompt and appropriate responses frequently minimize suboptimal outcomes. As with so many aspects of dental risk management, preparation is the key to the best possible result.

Appendix. Assessment Matrix for Swallowed/Aspirated Foreign Object

Note that this case presentation includes circumstances from several different closed cases, in order to demonstrate certain legal and risk management principles, and that identifying facts and personal characteristics were modified to protect identities. The content within is not the original work of MedPro Group but has been published with consent of the author. Nothing contained in this article should be construed as legal, medical, or dental advice. Because the facts applicable to your situation may vary, or the laws applicable in your jurisdiction may differ, please contact your personal or business attorney or other professional advisors if you have any questions related to your legal or medical obligations or rights, state or federal laws, contract interpretation, or other legal questions.

Additional Risk Tips content

Audio Records Reveal Flaws in Dentist’s Informed Consent Process

Dentists should be cautious recording patient visits. Learn how a dentist’s audio records became evidence against them in a malpractice case.

Informed Consent Process with Elderly Patient Spurs Lawsuit

Dentists need informed consent from patients deemed cognitively impaired. Read about how a patient refusal, ignored by a healthcare proxy, led to malpractice.

Patient Injured After Brick Flies Through Office Window

Dentists can be sued for the most unexpected adverse outcomes. In this case study, learn what happens after a brick flies through an office window.

This document does not constitute legal or medical advice and should not be construed as rules or establishing a standard of care. Because the facts applicable to your situation may vary, or the laws applicable in your jurisdiction may differ, please contact your attorney or other professional advisors if you have any questions related to your legal or medical obligations or rights, state or federal laws, contract interpretation, or other legal questions.

MedPro Group is the marketing name used to refer to the insurance operations of The Medical Protective Company, Princeton Insurance Company, PLICO, Inc. and MedPro RRG Risk Retention Group. All insurance products are underwritten and administered by these and other Berkshire Hathaway affiliates, including National Fire & Marine Insurance Company. Product availability is based upon business and/or regulatory approval and/or may differ among companies.

© MedPro Group Inc. All rights reserved.